As one of the three fasters who stood in front of Sikes Hall recently, I was asked a number of questions. Many of them were interesting and have led me to write this more formal reflection on fasting and protesting during the current period.

For those of us who find the Trump administration dangerous to higher education — as well as other areas of life — there is plenty of reason to protest. But I would like to bring things closer to home. Last year the administration, in response to the nine-day Sikes Sit-In, made a number of promises. Among them was the commitment “to more effective communications when malicious incidents occur and will use these as opportunities to articulate the negative impact on our sense of community.”

Last fall the Ku Klux Klan leafletted on campus. I, among others, contacted the university administration asking for a public statement that the sentiments expressed on the leaflet were not those of the University. No statement was forthcoming. The administration was silent. Finally, this week, after several days of waiting and a formal email from a group I am associated with, President Clements made a statement on a second set of KKK leaflets that appeared on campus.

This spring the Muslim ban has placed a number of our international students in very vulnerable circumstances. Many are afraid to visit their families in their home countries for fear of being barred from returning to their studies. Others are afraid of being deported should things turn worse. I, among many others, contacted the university administration to insist that they join the dozens of other public and private universities expressing opposition to the ban. Again, the administration was silent.

The fast was intended to call attention to the administration’s silence about the ban by way of showing solidarity with those in places like Aleppo who have no choice but to go without food. In that, it was successful. It was also successful in making many of the Muslim students on campus feel less isolated than the administration’s silence has led them to feel. We received expressions of real gratitude from many of those students, and for that we are grateful in return.

All marginalized students, staff and faculty at Clemson must bear in mind two things. These two things should create solidarity among African Americans, international students and professors, the LGBTQ community, women, the Hispanic community and others. First, as members of these communities know, they are vulnerable to hate, neglect and discrimination, particularly at present.

Second, the university administration will not protect you if it requires them to take any risk to themselves. As the administration’s recent actions have shown, it is the administration that the administration protects. Call it what you will — I call it cowardice — but at least recognize it for what it is.

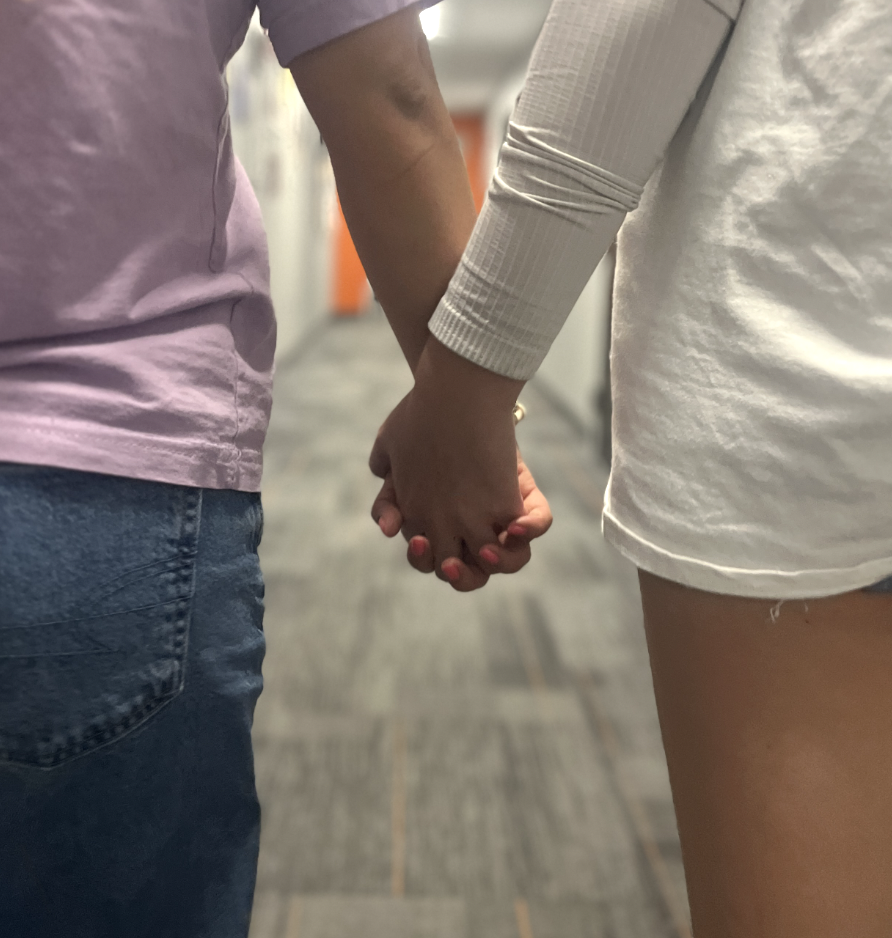

This means that the marginalized communities at Clemson and their supporters and allies have only one another to rely on. That is enough, but only if we aid one another. Only if we stand together each time one of us is subject to harassment or neglect. The struggle of the international students is the struggle of African Americans, which in turn is the struggle of women, the LGBTQ community, the transgender community, Hispanics and others. We must never forget that.

As the saying goes, we stand together or we fall apart. Those are our choices. And that is why we fast.

Categories:

OPINION: An introspective look at the ‘Fast of Silence’

Todd May, Professor of Philosophy

February 20, 2017

0

Donate to The Tiger

Your donation will support the student journalists of Clemson University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover