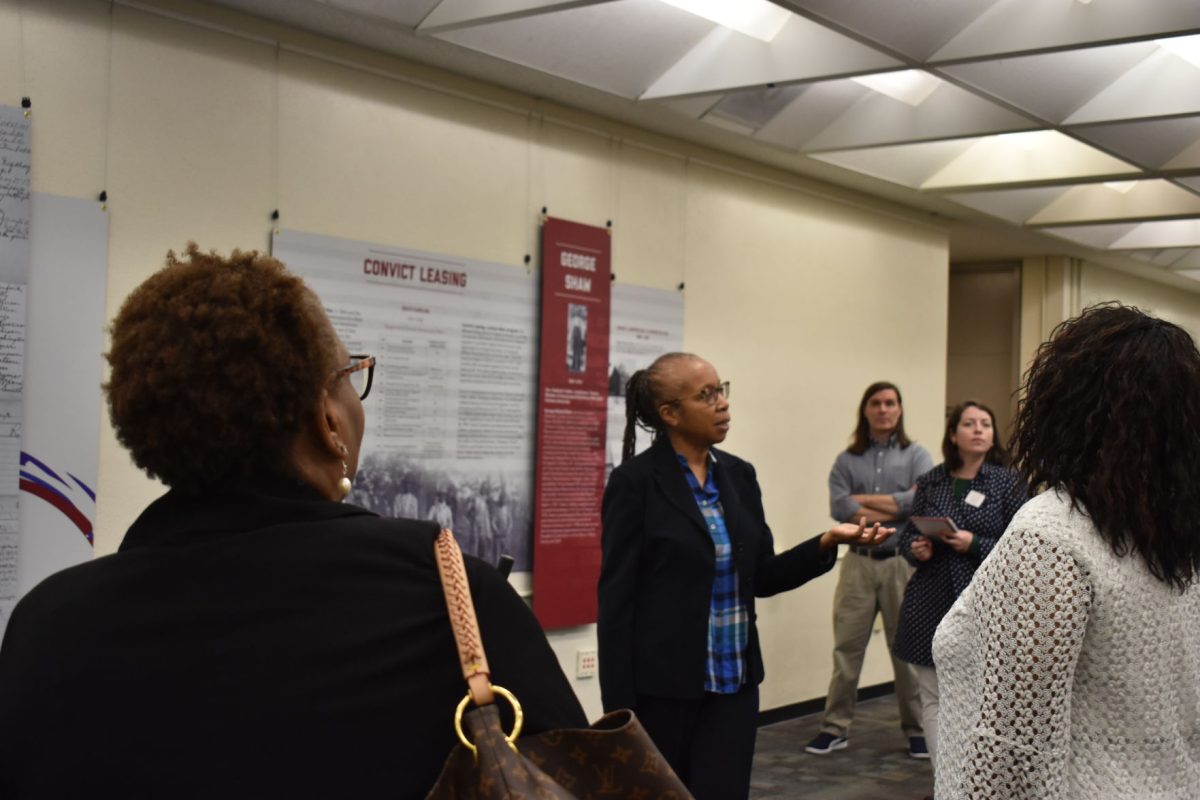

Right in time for Black History Month, the Call My Name project opened its preview of “The Making of the Black Clemson Community” expedition on Feb. 6, 2020 on the third floor of Cooper Library.

The project was created 13 years ago by Professor Rhondda Thomas. The project began when Thomas toured campus and learned that the university was built on John C. Calhoun’s plantation. “When I first came here, the story of slavery was not being shown at all,” Thomas said.

Thomas felt that the stories of the African Americans who built Clemson’s campus deserved to be known.

“We haven’t fully acknowledged our indebtedness to them for the existence of this university,” she said. “I felt that as a university, we had the responsibility to own all of our history and to make sure that history was shared with our campus community but also with the public as well.”

For the past 13 years, Thomas has been doing just that: informing the community of the contributions that slaves, sharecroppers and African-American convicts have built Clemson into what it is today.

“The most beautiful buildings on our campus, Tillman Hall, Hardin Hall, Sikes, Trustee House, were built by convicts as young as 13,” Thomas said.

Through her work, Thomas has been able to connect with countless relatives of the people whose names she has come across in her research. She says the part she is most proud of in the Call My Name project is finding names of the African Americans who built and worked on this campus when the school opened.

“We’re talking about people. The people are really important to me and so finding the identities of hundreds of people, I think, is the most important and significant part of my work,” Thomas said.

With these names, she has been able to reach out to the relatives of the early groups of African-American on campus.

One woman she was able to connect with is Adraine Jackson-Garner, who came to the opening of the preview to see her grandfather’s picture. Jackson-Garner runs the Littlejohn Community Center, which she started after college in honor of her grandfather, for whom the community center and basketball arena were named.

This year, Thomas is busy getting three projects ready on campus to continue telling the Call My Name story.

“Two of the three first African-American females who graduated from Clemson with four-year degrees are coming March 9,” Thomas said. “On April 1 we’re having a program that focuses on jazz…with Duke Ellington at the center…On April 8 and 9, there will be a two-day program focusing on convict labor.”

The big project, however, is the traveling exhibition coming next year. The exhibition will start at Clemson and then move across South Carolina to Georgia, North Carolina, Virginia and finally end in the Upcountry History Museum in Greenville, S.C.

“I would love to see it permanently installed on campus somewhere,” Thomas said. “That way, it would become a part of how we share our history as a university.”

The preview of the exhibition, which will be open until May 6 in Cooper Library, is meant to, in Thomas’ words, “provoke questions that can’t be answered.”

After saying some opening words, Thomas, who encouraged everyone to “share with others” the work being done, allowed the group to read about African American musicians and convict workers on the display posters, see plans for the new exhibition and use the large touch-screen interactive table to explore the stories of African Americans on Clemson’s campus.

Thomas was not the only one excited to show off her work at the preview opening. Designers Shelby Henderson, the director of the Bertha Lee Strickland Cultural Museum, and Nick McKinney, the director of the Lunney Museum, expressed their joy at the opening.

“Today is definitely the reward,” Henderson said. “Seeing people interact and being good with what they’re seeing and being interested and curious and taking the time to be apart of it.”

Henderson and Mckinney will continue to collaborate and work closely with Thomsa as they prepare the expedition for its tour. Like Thomas, they see the project as vital in their mission to, in the words of McKinney, “go back and tell the stories of people who had a major impact that never got recognized.”

“One of the elements that makes this an important story is that this is not just Clemson’s story,” Henderson said. “This is a national story that a lot of universities need to explore and tell. To be able to tell it and know it is a national story, it sends a message that everyone is starting to understand that the entire history of this country is important and not just one segment of our history.”

The full Call My Name exhibition plans to open in February 2021 on Clemson’s campus. The preview will be up on the right-side wall on the third floor in Cooper Library until May 6, 2020. For more information, visit callmyname.org.