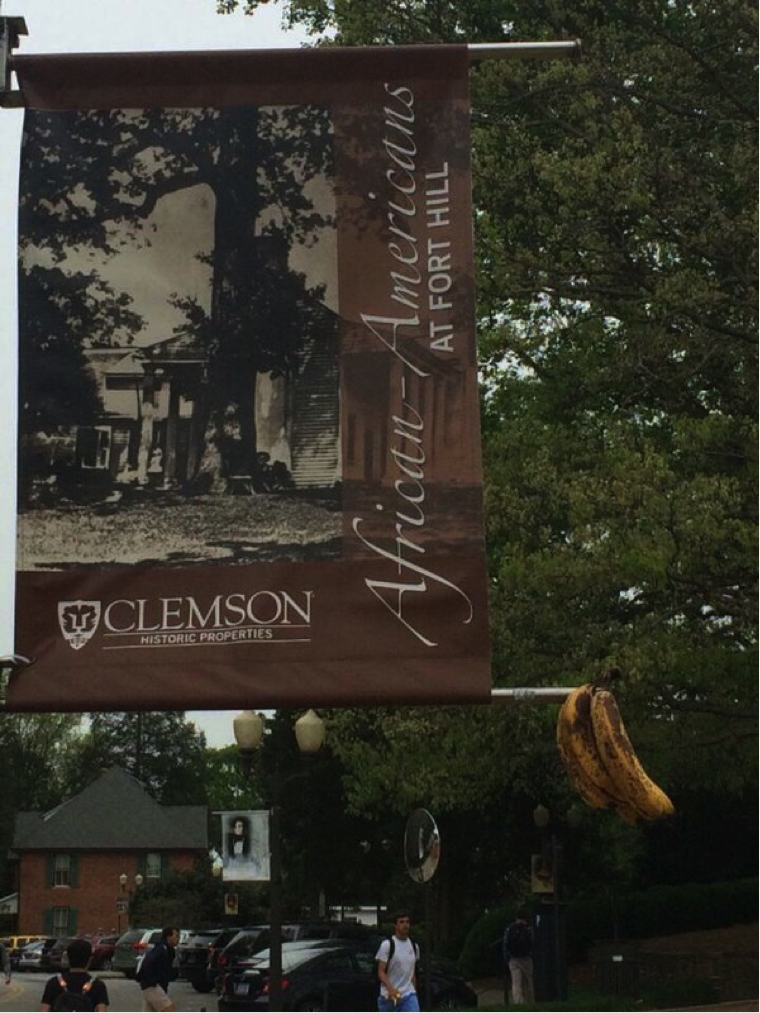

This is what some Clemson students, faculty, and staff saw on their way to school this Monday morning.

It is one of a series of banners on lampposts commemorating various aspects of life at Fort Hill. Fort Hill is the name of the plantation that Clemson’s founder inherited from his father-in-law, John C. Calhoun, and which sits in the middle of Clemson’s campus. Thanks to the efforts of students and faculty, especially Susanna Ashton and Rhondda Thomas, the story of this historic property has changed to reflect a slightly less sanitized version of the inevitably painful and violent history of a plantation house in South Carolina. Among these efforts are banners like the one in the picture, marking and documenting the presence of African-Americans in the history of Fort Hill. Clemson has a long way to go to come to terms with its history, a history that is interwoven with the realities of slavery, racism, segregation and the violence that attend them, but these banners were a small, visible step in the right direction.

This was the banner someone chose to deface this morning with a pair of bananas. At 1:25 that same Monday, Clemson University president James Clements sent a message to the entire campus community that read as follows:

Dear Campus Community: Earlier today a banner highlighting our University’s history was defaced. This type of conduct is hurtful, disrespectful, unacceptable and will not be tolerated. This incident is under investigation and we ask anyone with information to please contact CUPD at 864-656-2222 or Interim Dean of Students, Dr. Chris Miller at 864-656-5827.

Clemson University is committed to providing a safe, encouraging environment which supports and embraces inclusiveness at every level.

I was pleased to see a prompt response, though it left me wishing there had been a bit more to the message. I was sorry, but not surprised, to see the response to the president’s message on social media – among Yik Yakkers, sentiments along the lines of “pussies” needing to “grow thicker skin” because it was “just a couple of bananas” were prominent.

There is self-evident irony of (presumably white) students telling the black people with whom they share a campus built on a slave plantation to grow a thicker skin. And I just don’t have a lot to say about people using “pussy” as a slur in 2016. But the “just a banana” moment speaks to work that teachers and students in the humanities might be able to do together. We talk a fair amount about the history of racism, but maybe not enough about its semiotics. The banana ceased to exist as a banana the moment someone used it to adorn a sign commemorating African-American history at Clemson. In Saussure’s terminology, the banana becomes a signifier, and the signified it connects to is racism. (Saussure’s terminology is a little bit tricky here, as we have a material object (banana) representing a concept (racism), in place of the usual concept/sound image pair. This banana is not there to be made into bread, or sliced on someone’s cereal. It is there, manifesting itself as a racist signifier because the person who put it there did so with the express intent of creating a racist message.

In the event that someone claims mock innocence of the message (what’s the big deal about bananas?) here is a quick explainer they likely don’t actually need. At least in the popular imagination, monkeys and apes have a reputation for enjoying bananas. There is a longstanding tradition of insulting Black men and women by comparing them to monkeys and apes (trust me, or Google if you dare). News flash- it’s dehumanizing. And racist. There is no room for excuses when someone puts a racist symbol on a sign commemorating the often erased history of Black people in Clemson’s history.

If you don’t believe me, a visible manifestation of banana as racist symbol comes every now and again at a soccer match, where opposing fans throw bananas at a visiting Black player. A recent notable incident took place in 2014, when Villareal fans pelted Dani Alves of the visiting Barcelona squad with bananas. Alves responded by picking up the banana and eating it. It being the 20teens, the clip went, you guessed it, viral, and inspired famous soccer players to take pictures of themselves eating bananas as a way to stand in solidarity with Alves.

It’s an antiracist story that’s easy to feel good about, even as it embodies some of the classic aspects of the culture of slacktivism social media has wrought. At the same time, Alves performs a kind of semiotic alchemy – the banana thrown at him was a racist symbol; the banana he picked up and ate was, you guessed it, a banana. In that moment, in that arena, a famous athlete was able to flip the script on a racist fan. It would be a mistake, however, to make the Alves story into some kind of when life gives you lemons, make lemonade story for Clemson students of color. Telling students of color to turn lemons into lemonade comes pretty close to telling them to grow a thicker skin, which we have already ruled out as a response.

The lesson, if there is one, is not for the minority of the much-invoked “Clemson Family” who identify as people of color, but for the majority of this group, including this writer, who identify as white. Instead of telling Black folks to be a little tougher, I suggest that white folks challenge one another to be a little bit smarter. And by “smarter,” I mean “more empathetic.” The ability to see the world through another person’s perspective takes imagination, and imagination takes intelligence. Fortunately, the faculty of imagination, and the intelligence and empathy they entail, is one that can be exercised by reading, by looking, and maybe most especially by listening. It takes more energy to understand why someone is angry than it does to explain to them why they don’t deserve to be angry, but it might be worth the effort.

In this instance, consider what else all of us at Clemson might be talking about and working today instead of another racist incident? (I have papers to grade; you probably have papers to write, and None of us will get back the time we’ve spent on this.) It would not have taken much – statistically, the first person who saw the defaced sign was probably not a target of the racist message intended. If that person had bothered to remove the banana and thrown it away, there would be less hurt in the world today. Better still, if the person who defaced the sign had seen the opportunity to make a racist statement, and decided not to make the racist statement, we could be talking about something else. It’s 2016, and we have no time for these bananas.

Categories:

Yes, We Have No (Time For) Bananas

Jonathan Beecher Field, English Professor at Clemson University

April 11, 2016

Photo Contributed by Isiah Hamilton

Bananas hang from a banner which documents the African American history at Fort Hill plantation.

0

Donate to The Tiger

Your donation will support the student journalists of Clemson University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover