Literary adaptations have been cornerstones of cinema since the medium’s inception, as filmmakers have attempted to translate classic stories by great writers from written words into moving images. These adaptations’ success, however, has been variable, especially when the original writer’s prose style is so indelible that it forms an essential part of the book’s appeal. Often, the filmmaking simply cannot recapture the unquantifiable ways that the written word enhances the story.

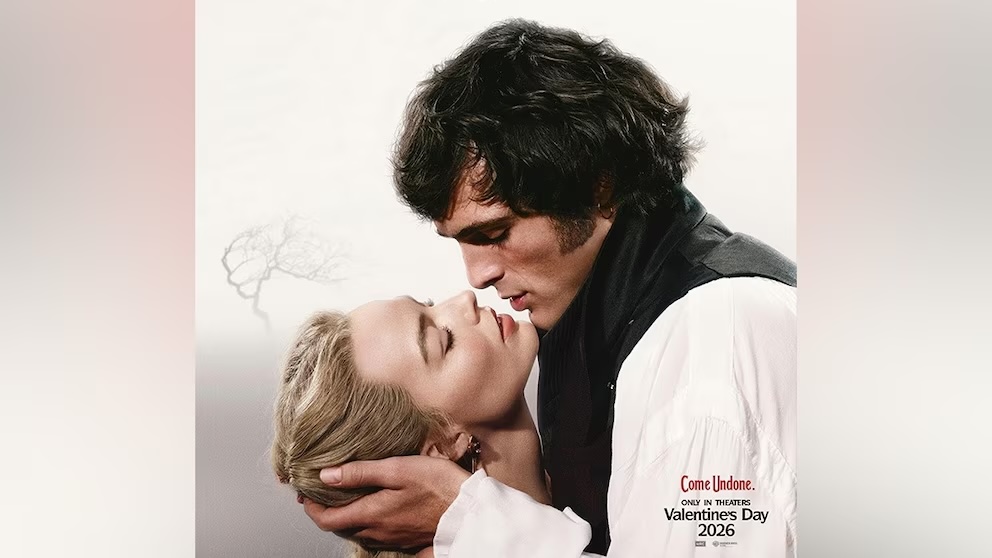

In his new film “The Swan,” based on a short story by the writer Roald Dahl, director Wes Anderson circumvents this issue in a way that is both simple and radical: he does not dispense with any of Dahl’s prose. The film is narrated by Rupert Friend, who delivers a subtle and nuanced performance as he speeds through Dahl’s beautifully rendered narrative.

“The Swan” is a very simple story and a very sad one. Two bullies of the brutish British type that Dahl loved to write happen upon a timid young birdwatcher. They torment the boy, Peter Watson, tying him to the tracks as a train passes over him. After he survives the ordeal, they force him to watch as they shoot and kill a nesting mother swan. After making Peter retrieve the murdered animal, they strap its wings to his arms and force him to climb up a tree so that they may hunt him as they hunt the bird.

Anderson and Dahl are two artists whose distinctive styles and senses of humor understandably but unfairly overwhelm the subtler qualities present throughout their respective bodies of work. Both men, despite the perceived light tone of their stories, are endlessly preoccupied with the profound sadness endemic to the human condition.

“The Swan” reflects Anderson and Dahl’s shared focus on sadness and cruelty, but it’s also the one that best typifies each artist’s belief in the ultimate triumph of good over evil. At the end of the film, the slim tree branch on which he is forced to stand breaks, and Peter takes flight. Borne aloft by the swan’s wings strapped to his arms, he flies home and crashes violently into his back garden.

Anderson does not depict Peter’s flight; Dahl himself, played by Ralph Fiennes, narrates it. Dahl describes how Mrs. Watson happens to look out her window right as her son comes crashing down into the backyard and how she rushes out to kneel by his side. Fiennes looks into the camera and takes a deep breath before reading what Mrs. Watson says to her wounded child. “My darling,” he recites, his voice wavering, “my darling boy. What’s happened to you?”

Even as he lies crying on the ground, physically and mentally damaged from the torture inflicted on him by two unfeeling boys who will likely never think of him again, Peter is loved. He has been driven beyond what Dahl refers to as “the point of endurance,” but he remains resilient, and he lives because he has something to live for.

In Anderson’s “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” Fiennes’ Monsieur Gustave says something that serves as a statement of intent for not only Anderson’s body of work but also Dahl’s: “there are still faint glimmers of civilization left in this barbaric slaughterhouse that was once known as humanity.” In “The Swan,” Anderson presents his most hellish vision of that slaughterhouse, but he refutes it with his most tender vision of those remnants of beauty.