Editor’s Note: This article was first published in The Chronicle of Higher Education, linked here.

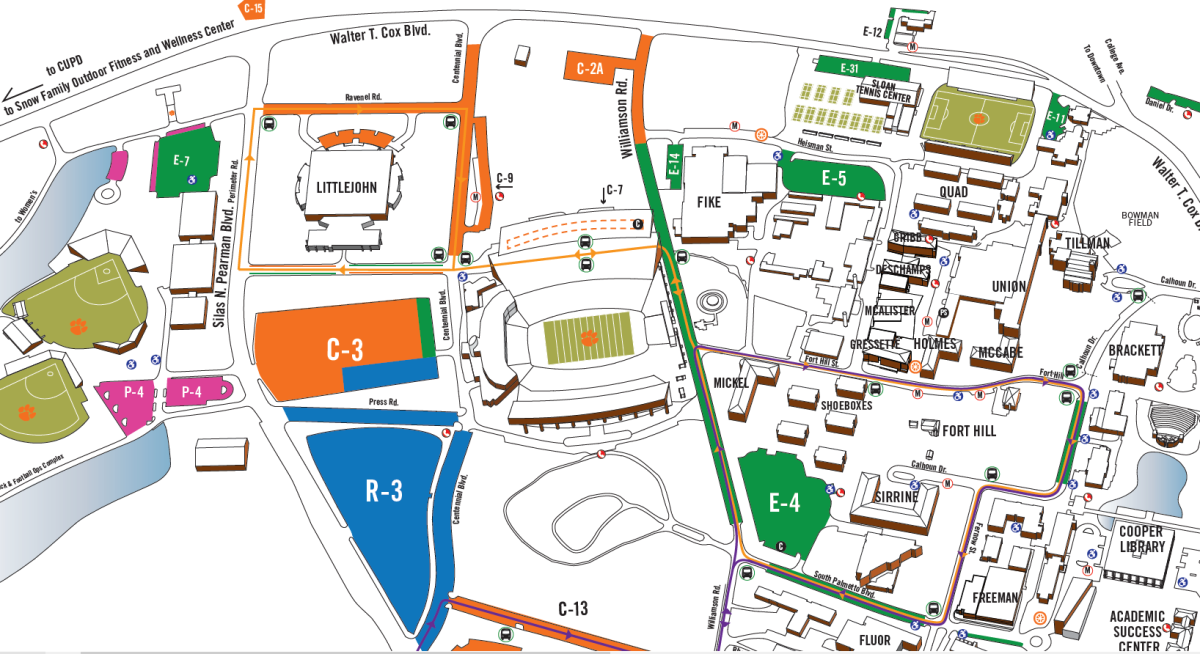

As is now well known, Clemson University recently terminated three employees — Joshua Bregy, Robert Newberry, and Melvin Earl Villaver Jr. — for social-media posts following the death of the conservative activist Charlie Kirk. The rationale for the firings was unclear from the start.

It began on September 12 with a communication that, while condemning posts about Kirk as “inappropriate,” emphasized Clemson’s commitment to the First Amendment and its intention to take “appropriate action” only “for speech that constitutes a genuine threat.” But soon after that, pressure from local and national politicians grew, along with calls to defund the university if the employees were not fired and assurances from the South Carolina attorney general that wrongful-termination litigation would not be pursued against Clemson on these matters.

University administrators quickly changed their tune. Just days later, Clemson announced that they had been fired for their “inappropriate” remarks, making a vague gesture to the university’s “commitment to cultivating an environment that is safe, respectful, and conducive to academic excellence” as the rationale.

The result of this shifting, amorphous justification for the terminations has been devastating to Clemson’s academic environment. Faculty, staff, and students no longer know what types of speech will be tolerated or punished. The larger upshot is a classic chilling effect — when people hold back from speaking because the boundaries of acceptable expression are unclear and the risks of reprisal too high. Reliance on elastic terms like “inappropriate” or “disruptive” leaves the community guessing what might cost them their jobs or their professional reputations. The result is self-censoring and silence.

Our own experiences illustrate this. One of us (Mike Gregory) wrote a highly critical op-ed in The State, one of South Carolina’s major newspapers, calling out the Clemson administration for punishing protected forms of expression after political outrage despite its official commitment to uphold free-speech rights. Clemson “has just demonstrated that it will function as a puppet of whichever political hand tugs the hardest,” Gregory wrote. The recent firings, he went on, show that Clemson is not in charge of Clemson. Gregory has also posted on social media using language similar to that which led to his colleagues’ terminations.

Meanwhile the other of us (Charlie Kurth) posted a sign on his office door that read, “My employer is morally bankrupt,” to critique how post-Kirk social-media posting had been handled by Clemson as well as recent, severe budget cuts at the university. A photo of the sign, as well as the office location and Kurth’s contact information, were subsequently posted on the X account of a former South Carolina state legislator, Adam Morgan, who added: “Seems the rot runs deep at Clemson.”

But in contrast to what happened to Bregy, Newberry, and Villaver, we have not been reprimanded. In fact, Bob Jones, the provost, not only wrote one of us saying, “I respect your opinions,” but we also understand that he pointed to our public critique as evidence of Clemson’s supposed commitment to free speech when speaking at a meeting of department chairs and associate deans. This, of course, is deeply ironic. Taking Clemson’s non-punishment of us for our public comments as an example of its support for free speech strikes us as no more plausible than someone claiming not to be a thief because they left a few dollars in the otherwise empty till.

More importantly, how can nearly identical speech lead to termination in some cases and tolerance in others? We wrote the provost for clarification but received none.

The only difference we see is that no powerful politician has yet demanded our firing. Our comments have circulated publicly, but it seems that because no influential state official seized on them, the administration has let us remain. That is the essence of arbitrary enforcement: The standard is not what was said, but whether it became the object of political outrage. This is the heart of the chilling effect. Faculty and staff must assume that any statement — even one squarely protected by the First Amendment — could lead to dismissal if it attracts the wrong attention.

But the negative impacts of the administration’s arbitrary decisions about what counts as free speech extend far beyond just what the two of us have experienced. Censorship pressures are trickling down. Some Clemson department chairs have advised faculty members to be quiet and keep their heads down. And while there is a letter-writing campaign aimed at bringing faculty, student, and staff concerns to the attention of the Clemson leadership, many balk out of fear of reprisal: “I don’t want to put my name on anything” is a refrain we repeatedly hear.

Predictably, these concerns are most pronounced for the more vulnerable members of the Clemson community: individuals from underrepresented groups, non-tenure stream and junior faculty, and those who are not American citizens. One department chair told his department, “I cannot protect you.”

Given the fear and plummeting faculty morale, the educational environment at Clemson is deteriorating too. Syllabi and lecture plans are being scrubbed of controversial topics: not only talk of race and gender in humanities classes, but also discussion of trade policy and immigration in business courses.

But it’s not just that our colleagues tell us that they are now much more cautious about what they say in class. They are also surreptitiously recording their lectures — insurance, they tell us, in case they get accused of saying something they didn’t say or their words are taken out of context. “I’m scared and I’m a tenured professor.” It goes the other way too: Faculty have learned that their lectures are being recorded without their permission and, understandably, think that students are “out to get us.”

What’s worse, Clemson is not an outlier. Around the country we are seeing administrators framing their responses to “inappropriate” comments by faculty and staff as matters of “civility” or “community values.” Yet what this means quickly shifts with the political winds and the public outrage of the moment.

At Texas A&M, Melissa McCoul was dismissed as a lecturer after a secretly recorded classroom discussion was posted online and branded “indoctrination” by a state legislator. Under political pressure, Texas’ Republican governor, Greg Abbott, demanded her termination, and within hours the university acceded. Officials invoked technical course-catalog discrepancies, but the recordings suggest the decision was driven by politics, not policy. Other parallels abound: Ball State University, the University of South Dakota, and more.

Across these cases, universities appear less guided by consistent standards than by external outrage. Terms like “disruption,” “misalignment,” or “institutional values” function as catch-alls, invoked only after political actors or social-media campaigns generate pressure. The result is a chilling effect in which speech protections hinge not on content but on who objects and how loudly. This dynamic illustrates the broader breach in the academic social contract, where institutions increasingly forfeit public trust by applying principles inconsistently and privileging short-term reputational management over enduring commitments to truth and civic responsibility.

It doesn’t have to be like this. Universities have the tools at their disposal to strengthen protections for academic freedom and open expression. They can publicly articulate clear and content-neutral standards, show through their actions their commitment to the principle that controversy and criticism are not themselves grounds for sanction, and insulate disciplinary decisions from political or donor influence.

At Clemson, we have worked to promote dialogue by, for instance, responding to all those who have written to us about our op-ed and sign. To our pleasant surprise, many of these have turned into productive conversations — even in cases where the original notes to us were nasty and aggressive. We have also written to Clemson’s senior leadership multiple times expressing a willingness to collaborate on constructive policies that foster free and respectful debate. But, unfortunately, here we have received no reply. The silence only reinforces the perception that “standards” are not standards at all, but ad hoc responses to political expediency. A genuine commitment to academic freedom would require transparency, consistency, and the courage to defend speech even when it provokes outrage.

— Charlie Kurth, professor, department of philosophy

— Mike Gregory, assistant professor, department of philosophy and religion

Letters to the Editor can be submitted to [email protected]. Letters should be in response to an issue on campus or an action by the University or city, or in response to an article, column, editorial or other content that The Tiger has recently published. Letters are published at the discretion of the Editor-in-Chief.