In today’s world, with name, image and likeness (NIL) deals and big brand college athletics, the idea of college athletes being paid and athletic departments gaining national recognition does not seem alien.

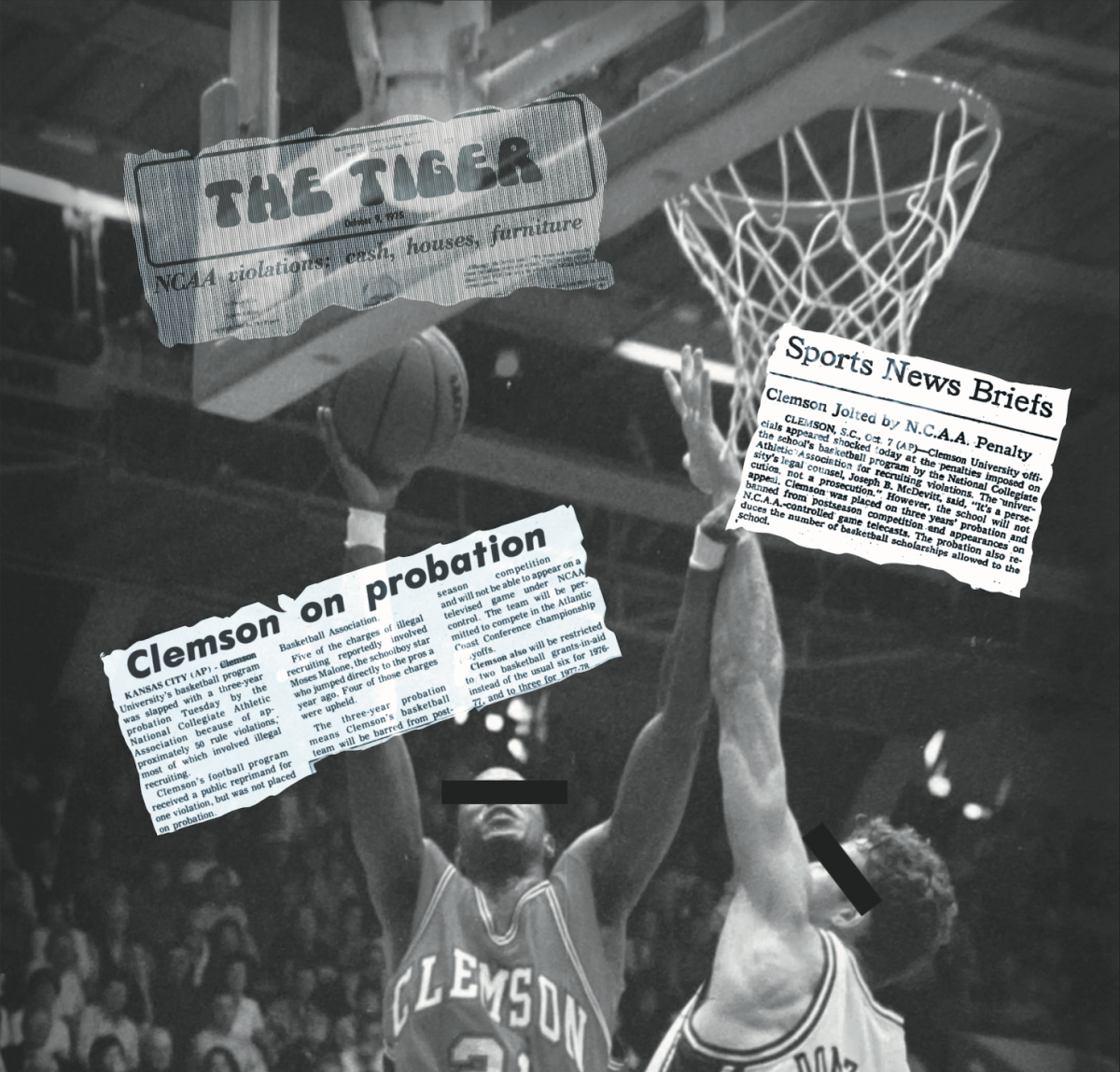

However, in the past, this concept was unfamiliar. In 1975 Clemson men’s basketball head coach Tates Locke was fired and the program was put on a three-year probation following recruiting violations, record tampering and player payouts by Locke.

As of today, Clemson basketball has played in 13 NCAA tournaments, signed current coach Brad Brownell to a $15 million, six-year coaching contract and is Clemson’s second-biggest revenue maker. But 47 years ago, the basketball program was on hanging on by the skin of its teeth.

Locke joined Clemson after four seasons with the University of Miami (OH) in 1970, where his team won a MAC conference title in the 1968-1969 season. Prior to that, he was the head coach at Army.

In the 1970s, athletic departments throughout the country were relatively small. Many colleges faced economic difficulties trying to keep their programs afloat and the lack of media coverage kept many programs out of the spotlight.

In Clemson, this challenge was also apparent. With no watchful eye assessing his team, Locke was able to buy recruits used cars and groceries for their families. Locke was also able to drag academic advisors into his scheme, where they would alter athletes’ academic records in order to keep their playing eligibility.

Locke and a former Clemson football player even went as far to create a disguised “fraternity” that appealed to prospective African-American student athletes to promote the inclusion that Clemson was lacking in the 1970s.

With more cheating came more Clemson success. In 1970, Clemson’s basketball record was (9-17). By 1974, Locke coached them to a (17-11) record, drastically helping the program.

After NCAA officials became suspicious based on recruiting grounds, an investigation began. Shortly thereafter, Locke’s activities were exposed. He resigned in 1975, just four seasons after he started at Clemson.

The NCAA put Clemson on a three-year probation for between 1975-1978. Clemson was charged with forty violations, including illegal academic assists and unrightful scholarships.

Locke went on to write “Caught in the Net,” his biographical tell-all on the NCAA investigation. In his book, he described his violations and the turmoil it caused him as a “repercussions.”

As for “paying off” players, college athletes can now make money off their NIL, thanks to the rule change by the NCAA in July of 2021.

“I really thought I was going to die after Clemson… Why I didn’t commit suicide or have a nervous breakdown I’ll never really know,” Locke wrote.

The book was published in 1982 after his two-year coaching career with Jacksonville University. He had been forced to resign, this time because of pressure from the athletic department, according to Locke.

In spite of Locke’s violations and the inevitable setbacks they caused, Clemson was able to make a tournament appearance in 1980 in its comeback season.

The Tigers’ current head coach, Brownell, joined in 2010. In his twelve seasons with Clemson, Brownell has helped Clemson succeed without any NCAA violations.

As for “paying off” players, college athletes can now make money off their NIL, thanks to the rule change by the NCAA in July of 2021.

For comparison, Wayne “Tree” Rollins went on to play in the NBA after his time at Clemson with Locke. In an interview with Sports Illustrated in 1982, Rollins admits that he was “getting about $14,000 a year.”

“That’s counting the money paid for my Monte Carlo [car], the clothing allowances, gas money and pocket money.”

While this money was from the university program, athletes in today’s athletic landscape can make more than that in one corporate deal alone.

Clemson quarterback DJ Uiagalelei’s Dr. Pepper endorsement deal that ESPN and Sports Illustrated project to make him over $1 million by the end of his college career.

In more recent weeks, the NCAA has announced they are reviewing NIL policies due to potential recruiting violations and the impact it has on a student-athlete program commitment. NIL deals are suspected of skewing an athlete’s decisions based on how much money and recognition they can get from a collegiate program.

44 years after Clemson’s probation expired, the basketball program has seemed to maintain its integrity and steer away from NCAA violations. Still, with the surge of NIL endorsements, the 1975 scandal provides historical context for college athletes receiving money.

With NIL, today’s starts in Clemson Athletics have the opportunity to make substantial amounts of money. Clemson basketball and collegiate athletics have come a long way since 1975, and Locke’s infamous legacy is a reminder of how not to follow rules and regulations.