For her 14th birthday, Marion Reeves’ brother brought home a cookie cake from the grocery store. Rather than feeling happy to celebrate her birthday, Reeves was mortified.

Throughout middle school and high school, Reeves struggled with an eating disorder. What began as a desire to eat healthier soon morphed into something much uglier. As a young girl seeking acceptance from her peers and a cross-country runner trying to improve her athletic performance, Reeves found herself susceptible to the pressures mounting all around her.

Her family began to notice that something was wrong after a few months. They took her to the doctor and she was diagnosed with anorexia, a disorder she had never even heard of. “I didn’t really realize what I was doing was an eating disorder,” she says. Reeves compares her battle with anorexia to an addiction, explaining that seeing the number on the scale decrease gave her a sense of satisfaction and motivated her to lose more weight.

That first doctor’s visit was the start of a long road of seeing therapists, dietitians, medical doctors and psychiatrists throughout her middle and high school years. Reeves had to overcome not just the physical aspect of the disorder, but also the mental health challenges associated with it.

“Once I finally was in a weight-restored body and got back to what was healthy for me, it didn’t mean that all of the thoughts went away,” Reeves says. “In some ways, I’d say that they got worse because it wasn’t as visible from an outside perspective that I was struggling.”

In addition to her battle with anorexia, Reeves struggled with depression, which she believes was largely a result of isolation from her peers. She was hesitant to spend time with friends out of the fear that she might encounter an uncomfortable situation involving food or that people would comment on her body.

After years of working to overcome those challenges, Reeves finally found herself in a healthier body and mindset, so she embarked on her next journey as a psychology student at Clemson University. After graduating with her undergraduate degree in 2018, she went on to receive her master of clinical and mental health counseling from Clemson in 2020.

Now, more than ten years since the onset of her eating disorder, Reeves is a therapist who works with patients struggling with eating disorders and other mental health issues like anxiety and depression. “I’ve really enjoyed that, getting to be on the other side of things and have that firsthand experience of knowing what it’s like to be the client and dealing with these struggles,” she says.

The Big Picture

A joint study conducted by several top eating disorder institutions, including a program based at the T.H. Chan School of Public Health at Harvard University, found that 9% of the US population will suffer from an eating disorder at some point during their lifetime.

Teens and young adults are particularly at risk for the development of an eating disorder. The National Institute of Mental Health reports that the median age of onset for anorexia and bulimia is 18, while the median age of onset for binge eating disorder is 21.

Risk Factors

Some people are more likely than others to develop an eating disorder due to a range of risk factors. “There is what we call a bio-psycho-social contributor to the development of an eating disorder,” says Dr. Sydney Brodeur-Johnson, the Senior Director of Clinical Services at Veritas Collaborative, a national healthcare system for the treatment of eating disorders. “What that means is that it’s a combination of some genetic predisposition or vulnerability combined with socially how we experience the world.”

The National Eating Disorders Association, or NEDA, groups risk factors for the development of an eating disorder into three categories: biological, psychological and social.

Biological risk factors include having a close relative (like a parent or sibling) with an eating disorder; having a close relative with a mental health condition like anxiety, depression or addiction; having a history of dieting and having type 1 diabetes.

Psychological risk factors include perfectionism, dissatisfaction with one’s body image and having anxiety disorders like generalized anxiety, social phobias and obsessive-compulsive disorder. In Reeves’ case, she believes her “type-A, perfectionistic, all-or-nothing personality” led to her diet spiraling out of control and becoming an eating disorder.

Social risk factors include discrimination or stereotyping based on weight; teasing and bullying based on weight or bodily characteristics; loneliness and isolation; and susceptibility to the socially-defined ‘ideal body.’

Brodeur-Johnson says we live in a society that is overly-committed to the diet-culture mentality. “There is a lot of expectation for how we engage with food or how our bodies look,” she says. “There is a huge push or drive for thinness and idealizing that thin body.”

In most cases, biological, psychological and social risk factors combine to create what Brodeur-Johnson calls the “perfect storm of stressors” for the development of an eating disorder.

Signs of an eating disorder

The signs of an eating disorder range from a preoccupation with weight and bodily characteristics to excessive dieting to noticeable fluctuations in weight, though not all eating disorders can be recognized by weight loss.

“You can’t always notice outward signs of an eating disorder…it’s not always someone being underweight,” says Reeves. “There can be all types of eating disorders, so you may not always visibly see it but sometimes you can notice shifts in how someone is acting.”

Behavioral signs of an eating disorder include refusing to eat certain foods or food groups, having rituals around food, skipping meals and withdrawing from social activities. Physical signs include stomach cramps, menstrual irregularities, difficulty concentrating, fainting, frequently feeling cold, having dry skin and hair and having dental problems such as tooth decay.

You can find more information about the warning signs and symptoms of eating disorders on this page from NEDA.

College life—the perfect storm

Leaving home to go to college is an exciting, albeit scary time for many people. Going to college brings many new opportunities and allows people to experience independence away from their families, but it can also present a host of unfamiliar challenges.

According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, the most common age of onset for eating disorders is between 12 and 25, putting college students right in the middle of the age group most at risk.

“Students are trying to figure out how to feed themselves, how to make sure they get their work done, how to engage in social groups, [and] how to fit in,” says Brodeur-Johnson. The combination of all these new stressors at once can be a catalyst for the development of an eating disorder, especially for people who are already genetically predisposed to eating disorders.

Brodeur-Johnson says one behavior known to trigger an eating disorder is a diet, and “when people feel pressure from an athletic group or a sorority or a peer group that they are going to be more included if they look or behave in a certain way with food,” this can cause a diet to escalate into a full-blown eating disorder.

A national survey of eating disorder programs and resources at 165 colleges and universities in the US found that at most schools, screenings for eating disorders are lacking. Less than a quarter of the schools surveyed offered year-round screenings to identify people who may be struggling with an eating disorder, and early detection is one of the most important factors in successful treatment.

Furthermore, less than a quarter of the schools surveyed provided training for fitness instructors and dieticians on identifying signs of an eating disorder. In order to remedy these unmet needs, colleges and universities can add eating disorder screening questions to doctor’s appointments and provide more training opportunities for those in a position to identify students who may be suffering from an eating disorder.

Pandemic stressors

“The pandemic is really creating a crisis around people with eating disorders,” says Brodeur-Johnson. She points to the isolation and anxiety of the pandemic as leading causes of a rise in the number of cases and increase in severity of cases of eating disorders, substance abuse, depression and anxiety.

A study published in the International Journal of Eating Disorders in July 2020 found that 62% of people in the US with anorexia had experienced a worsening of symptoms since the start of the pandemic. The survey also found that 30% of people in the US with bulimia or binge-eating disorder had experienced a worsening of symptoms in the same time period.

Fortunately, the pandemic has allowed health care providers like Veritas Collaborative to provide some outpatient care virtually, giving many people easier access to the care they need.

Eating disorders don’t discriminate

Brodeur-Johnson is the executive chair of the equity, diversity and inclusion council at Veritas Collaborative and specializes in providing multiculturally competent care. She emphasizes that all kinds of people can suffer from an eating disorder. “We have this myth that we have bought into as a culture that only white, young, straight girls get eating disorders and that’s not true,” she says.

People of all different races, ages, genders and backgrounds can suffer from an eating disorder. However, some groups are more likely to develop an eating disorder than others. The Duke University Health System reports that 30-50% of transgender people suffer from an eating disorder, a statistic that is drastically higher than that of the general population.

Some groups are also more likely to be discriminated against when seeking treatment for an eating disorder. A study conducted by NEDA in 2006 found that when provided with identical case examples for white, hispanic and black women, 44% of clinicians found the white woman’s eating behavior problematic, 41% found the hispanic woman’s eating behavior problematic, and just 17% found the black woman’s eating behavior problematic. The clinicians were also less likely to recommend that the black woman seek treatment.

Eating disorders among athletes

As a cross-country and track athlete in high school, Reeves felt especially pressured to have a lean body type. Long distance running and other ‘lean’ sports like gymnastics and diving can create the perfect set of circumstances under which an athlete can develop an eating disorder.

Up to 47% of elite female athletes in sports that emphasize leanness have experienced eating disorders, according to a study conducted in 2008.

“With running as a sport in general, there can be a lot of focus on having a certain body type, being lean and a lot of comparison,” says Reeves.

Collegiate athletes must manage a particularly stressful environment, often balancing many hours of practice per week and a full-time course load.

A national survey of eating disorder programs and resources at 165 colleges and universities in the US found that only 22% of athletic departments at the schools surveyed provided screening and referrals for student athletes showing signs of an eating disorder.

Moreover, only 2.5% of the athletic departments provided year-round prevention and education programs for athletes in high-risk sports like gymnastics, wrestling and swimming.

Brodeur-Johnson says that in order to create a safer and healthier sporting environment, coaches, teammates and parents should refrain from making comments encouraging athletes to lose weight or implying that they would be faster or more competitive if they lost weight.

She also emphasizes that the most important thing is balance. Athletes should not be encouraged to exercise or practice to the point of exhaustion or when they are sick. Rather, they should strive for balance between time spent on their sport, time spent on their academics and their social lives.

“It really is about supporting the student as a whole person as opposed to just expecting that their whole life revolve around how they perform in their sport,” says Brodeur-Johnson.

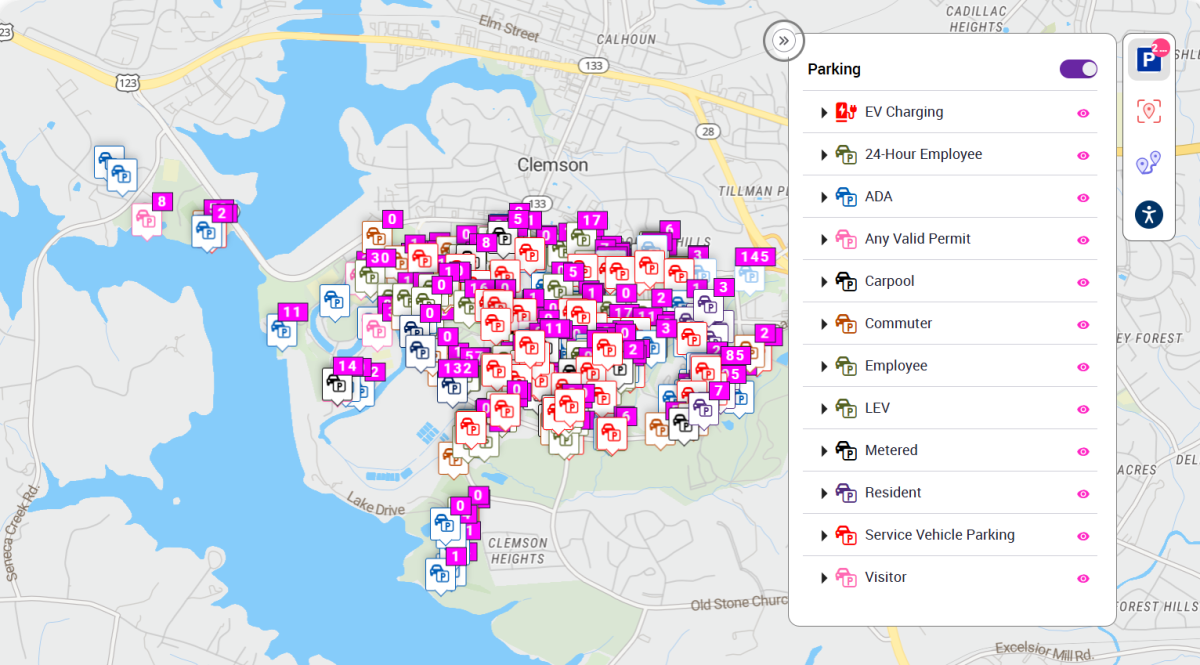

Student athletes at Clemson University can see a psychologist trained specifically in athletics and should contact CAPS for more information.

What to do if you think someone you know has an eating disorder

If you suspect someone you know may be suffering from an eating disorder, the best thing you can do is approach that person in a kind and gentle way and calmly let them know that you are worried about them.

“The best thing you can do is voice your concerns through “I” statements and encourage them to seek help,” says Morgan Robinson, the Eating Disorder Services Coordinator at CAPS. “Be prepared for a negative reaction as many times the person struggling is unable to see the harm in their behaviors; remain caring yet firm and continue to bring up your own concerns without placing blame or stigma on the behaviors or person.”

Someone with an eating disorder may react negatively when you show concern for them because eating disorders are ego syntonic – meaning people are attached to them and the disorder may serve some purpose, such as providing a feeling of control. People struggling with eating disorders may also be irritable or sensitive as a result of malnourishment.

Brodeur-Johnson suggests bringing up behavioral examples to explain why you are concerned about the person, like ‘I noticed that you go to the bathroom after you eat and stay in there for a while and I wonder if maybe you’re making yourself sick’ or ‘I noticed that you only seem to eat very little and that what you choose to eat is pretty restrictive and that’s concerning to me and I care about you.’

If the person you are concerned about is a Clemson student, you can file a CARE Report through the Office of Advocacy and Success and you have the option to make the report anonymous.

As a friend, you can offer simple things like walking to Redfern with the person you are concerned about or calling to get more information about the eating disorder treatment program.

If the person you are worried about continues to reject your efforts to help, you shouldn’t feel bad about filing a CARE report or getting another adult involved, like their parent, a teacher or an RA.

“It can be difficult to know how, or if it’s appropriate or when to do something, but I think it’s really critical that college students understand that if they’re seeing something and somebody is really having a hard time, they might be the only one who knows that they’re suffering,” says Brodeur-Johnson. “When people are suffering, they need help to get care.”

Reeves says early intervention is important for the successful treatment of eating disorders. “The earlier someone—whether it’s a friend, a parent, a sibling—can jump in and bring to light what’s happening, the better the outcome can be.”

Reeves encourages anyone who is suffering to seek care. “It’s okay to get help for mental health problems. It’s okay to struggle with something and there’s no shame in saying ‘I have a problem I need to get help for.’”

If you have a friend or loved one who is dealing with an eating disorder, you should try to be a good listener and validate the person’s feelings. It can also help to keep talk away from food and to provide positive distractions, like making the person laugh.

It is important to show compassion toward loved ones who are struggling with eating disorders.

“If you don’t have an eating disorder, it can be really hard to understand the thoughts behind it and to understand how hard it can be to pick up the fork, get the food and put it in your mouth,” says Reeves. It’s something that seems so simple but for someone with an eating disorder, it’s so much more complex.”

Treatment options at Clemson University

Clemson’s Counseling and Psychological Services department (CAPS) offers an eating disorder treatment program for Clemson students. The first step in seeking treatment for an eating disorder at Clemson University is to contact CAPS to schedule an initial phone screen and take an initial assessment. If the student is determined to be appropriate for the eating disorder treatment program, they will be contacted by the program coordinator to discuss how to move forward.

According to Robinson, many factors must be considered when deciding the appropriate level of care for a patient with an eating disorder. These factors include medical stability, lab results, number and severity of behaviors, the length of the disorder and willingness for treatment. Patients with less severe cases can undergo outpatient therapy, while patients who need more attention may be referred to an intensive inpatient program, partial hospitalization program or residential program.

If a Clemson student is a good candidate for outpatient therapy, they will have an appointment with CAPS once per week. CAPS also offers group therapy sessions, though these are not specific to eating disorders.

Appointments with CAPS and doctor’s visits at Redfern Health Center are covered under the Student Health Fee, which is paid by all students enrolled in six or more on-campus credit hours. The student health fee costs $182 per semester, or $66 per summer session (as of March 2021). The fee excludes lab work and some other additional services. Students enrolled in entirely online coursework may not have paid the health fee at the start of the semester and should consider paying the fee before seeking treatment from CAPS or Redfern Health Center.

A multidisciplinary team is necessary for the treatment of an eating disorder in order to address not just the medical aspect of the disorder, but also the mental and psychological aspects. Robinson recommends that patients seeking treatment from CAPS for an eating disorder also seek care from a medical doctor through Redfern Health Services and a dietitian or nutritionist that specializes in working with patients with eating disorders. CAPS does not currently have a dietitian or nutritionist on staff, but recommends working with a local provider; the cost of these services is not covered by the student health fee.

Due to state law, CAPS is unable to treat students while they are outside of the state of South Carolina. If a student goes home over the winter or summer break and wishes to continue their treatment, they can have virtual appointments—as long as they are still residing within the state of South Carolina and meet the criteria set by CAPS.

For students who reside outside the state of South Carolina during breaks, CAPS can consult with community providers in order to help facilitate the continuation of appropriate treatment.

Perfectly Imperfect

After several years of hiding her eating disorder and making excuses to her friends about why she was going to so many doctor’s appointments, Marion Reeves decided enough was enough. She began to be more outspoken about her struggles, and through her vulnerability, she connected with others going through the same thing.

When she was 19 years old and a sophomore at Clemson University, she started writing her book, “Perfectly Imperfect,” about her battle against anorexia. She made sure not to include any specific numbers about weight or calories in order to make the book more comfortable for people actively struggling with an eating disorder to read.

Her mom even wrote a chapter near the end of the book to share her experience as a parent of someone battling anorexia.

The book was published when Reeves was 20 years old, and then came the outpouring of support. People reached out to thank her for sharing her experience, as they had gone through something similar or had witnessed a loved one struggle with an eating disorder.

Reeves says her experience with an eating disorder has altered the course of her life—motivating her to become a therapist in order to help people dealing with a disorder she once experienced herself.

Her advice to young people who are in the same situation she was in when her brother brought home a cookie cake for her fourteenth birthday is to surround yourself with body-positive and food-positive people.

“The way your body looks doesn’t change your worth,” she says. “Your worth does not increase or decrease based on the size pants you wear, the number on the scale, or the amount of calories you eat. Find those things that make up your worth and who you are as a person that don’t have to do with your appearance but with your intrinsic value…Recovery is possible, even if it’s really hard sometimes.”