As students returned to Clemson’s campus for the spring 2024 semester, 22 buildings on campus were stocked with free emergency overdose reversal kits as a response to the nationwide fentanyl crisis.

In the near future, the University plans to expand the ONEbox kits to include them in other areas of campus, with Student Health Services working on a protocol to find future locations, Jennifer Goree, the director of Healthy Campus, told The Tiger in an interview.

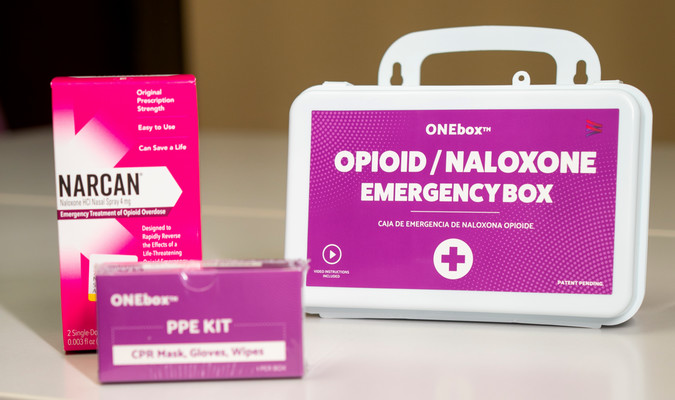

These ONEbox kits include Narcan and a quick training video on how to respond to an overdose emergency as the result of a collaborative effort between Public Safety, Student Health Services, Clemson Rural Health and the South Carolina Department of Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse Services, according to a Clemson News article.

“This is our first round of having these kits,” Goree said. “We are working on the where and why we put them in certain buildings, and we are analyzing high-traffic locations around campus using card swipes, building usage and other metrics. There will be more to come in the future as we find the right locations for them.”

Student Health Services claims that this is the best practice all over the state and that neighboring schools, such as the University of Georgia and the University of South Carolina, have adopted similar practices for overdose prevention.

Clemson’s combative efforts

Since 2022, Clemson University has taken proactive measures to combat fentanyl from harming students and members of the local community due to the rise in overdose cases.

When Maya Khaskhely, a Clemson student senator, first spoke with student health officials in November 2022, Narcan was available at a cost to students on campus from the Redfern Heath Center pharmacy and not located anywhere else on campus.

“Before coming to Clemson, I had heard about universities and colleges throughout the U.S. having Narcan distribution programs on-campus. When I came to Clemson, I was surprised to see that it wasn’t a thing here. I did a lot of research on Narcan distribution programs at universities similar to Clemson and a lot of them had one,” Khaskely said in an email to The Tiger.

Khaskely shared that during the 2022 school year, she emailed Kimberly Poole, the assistant vice president and senior associate dean of students, and the Clemson University Police Department to ask if they had knowledge of a Narcan distribution program at Clemson. They both said that it did not exist.

After learning there was no action being taken, Khaskely met with George Clay, the executive director of Clemson’s Redfern Health Center, to discuss how to bring Narcan on campus and to convince him that this was a needed program.

“He seemed pessimistic at first,” Khaskely said. “After the Governor and South Carolina Department of Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse Services announced their initiative to prevent opioid overdoses in SC, Dr. Clay was more optimistic of the potential to put Narcan on-campus.”

After student initiatives and the growing concern at the state and national level, ONEbox kits became available on campus on Jan. 8 and at no extra cost in limited numbers to students who request them from Student Health Services and want to have them off-campus in case of an emergency, according to Kelley Metcalfe, the Clemson Healthy Campus associate director for alcohol and other drug initiatives.

How the nationwide crisis has affected South Carolina

Greg Mullen, Clemson University police chief and vice president for public safety, is particularly concerned about the fentanyl crisis affecting Clemson in the future.

“The prevalence of fentanyl in counterfeit prescription drugs is a serious problem,” Mullen said in a Clemson News article. “While we’ve been fortunate to avoid any such incidents at Clemson, the impact of accidental poisonings and overdoses is happening on college campuses across the U.S., including the deaths of three college students from fentanyl poisoning in North Carolina in just the last two years.”

At the national level, including South Carolina, the synthetic opioid fentanyl is largely responsible for the increase in overdose deaths, according to a South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control news release. In South Carolina, drug overdose deaths involving fentanyl increased by over 35% from 2020 to 2021, while fentanyl also played a role in over two-thirds of all opioid-involved overdose deaths in 2021.

The local Clemson community has seen drugs, pills and other consumable items laced with fentanyl in recent months that warrant concern, according to Clemson University Public Safety.

The Clemson University Public Safety Facebook page issued a warning on Jan. 11 about a dangerous and lethal drug disguised as colorful candy, stating that “Fentanyl remains the DEADLIEST drug threat facing our country and communities. It has recently been seen in a variety of bright colors, shapes and sizes.”

The warning came just one day after Anderson County Sheriff’s Office investigators announced that officers spotted a parking lot drug deal that led to the confiscation of over 10,000 ecstasy pills. The pills weighed over seven pounds and were disguised as Lucky Charms, according to a WYFF News 4 article.

In addition, South Carolina Attorney General Alan Wilson announced on Jan. 3 that five indictments were unsealed in a narcotics trafficking investigation. In total, five indictments against 64 defendants on 327 narcotics and related charges were issued in three Upstate counties. That investigation has primarily focused on fentanyl trafficking and associated overdoses.

“Of particular interest is that the State Grand Jury has indicted alleged fentanyl dealers for murder, accessory before the fact to murder, and conspiracy to commit murder for their alleged role in distributing fentanyl to victims who died from resulting overdoses,” the South Carolina Attorney General’s office states.

The future fight against fentanyl

Clemson Student Health Services does not think that opioid prevention kits will decrease or go away altogether, but rather that the kits will be seen in all types of schools, not just colleges or universities.

“Hopefully, it will grow to be something to expect in a public setting to see Narcan. I don’t think we are there as a society yet, but we are headed in that direction,” Goree said. “We will probably see all schools with kits like this in the future, as fentanyl is not just found in drugs, but things like candy and consumable foods. Children in primary schools have had to be taken to the emergency room because of fentanyl being ingested.”

Clemson University has worked with its police department in a team effort to incorporate the new prevention kits into the online Aspire to Be Well program, a program that aims to educate students on Clemson health and safety measures before they step foot on campus.

Goree acknowledged that Clemson Student Health Services is aware that students sometimes take prescription pills or opioids that were not legally prescribed and that there is no perfect solution to the problem.

“With students that are at a higher risk of participating in such activities, the best option is to have friends ready to administer Narcan if needed. There is no way of knowing if fentanyl is in a pill without testing it,” Goree said.

The University is unable to give students fentanyl test strips because there is a sense of liability if they are not accurate and have a false positive result. However, test strips are available to the public, with SCDHEC Public Health Clinics providing free opioid overdose kits.