A $50,000 reward was offered last fall to anyone willing to provide information about the death of Clemson freshman Tucker Hipps on Sept. 22, 2014. By December, the reward had increased to $100,000, but has yielded no substantial leads in the case.

“Since the reward increased, [Crime Stoppers of Oconee County and investigators] have gotten a few tips in, but that’s really been about it,” said Jimmy Watt, public information officer for the Oconee County Sheriff’s Office.

The lack of information has left Cindy Hipps, Tucker Hipps’ mother, wondering if she will ever learn what really caused her only child to fall to his death from the Highway 93 bridge over Lake Hartwell.

“Come talk to me,” said Cindy Hipps in an interview with The Tiger. She encouraged anyone with information regarding the specifics of her son’s death to reach out to her directly. She believes a lot of healing still needs to occur and that the deeper truths of what happened to her son must be weighing heavily on somebody.

According to court records and the police, the fraternity brothers who accompanied Tucker Hipps on the pre-dawn pledge run of Sept. 22 did not report him missing until 1:15 p.m., which was more than seven hours after the incident.

Police found Tucker Hipps’ body floating in Lake Hartwell under the Hwy. 93 bridge. An autopsy later concluded that the freshman’s death was the result of blunt force trauma. He was in his first month at Clemson when he died.

Tucker Hipps studied political science and had plans to go to law school. He had been elected Sigma Phi Epsilon’s “pledge class president,” which meant he served as the liaison between the pledges seeking full membership and fraternity leadership.

The Hipps family claimed in court records that some of the SPE brothers who organized and led the run were “deceptive” and not “forthcoming” with police regarding what they knew of the death. Members of the fraternity had deleted text messages and some attempted to delete cell phone records in the hours and days after the event, according to records. Cindy Hipps and her attorney, Jennifer Burnett, filed a lawsuit in April 2015 in the Pickens County Court.

The lawsuit sought more than $25 million in damages from a list of defendants it claimed were responsible for Hipps’ death. Included in the list was Clemson University, the South Carolina Beta Chapter of Sigma Phi Epsilon, Sigma Phi Epsilon Fraternity, Inc. and three members of Clemson’s SPE chapter who organized the 2014 pre-dawn run: Thomas Carter King, Campbell T. Starr and Samuel Quillen Carney, the son of Delaware Governor John Carney.

In the first three weeks of the fall 2014 semester, Clemson authorities began investigating complaints that alleged code of conduct violations by SPE and other fraternities, according to the lawsuit. SPE members learned that Clemson was eyeing possible suspension of their fraternity for violations involving “hazing and sexual misconduct.”

In his role as pledge class president, Tucker Hipps was ordered to bring “30 McDonalds biscuits, 30 McDonalds hash browns and 2 gallons of chocolate milk to the fraternity hall” before the run started. He did not meet these expectations leading to a “confrontation” between him and King.

The lawsuit asserts that SPE’s plan for the 5:30 a.m. pledge run on Sept. 22 was “not permitted under the Sigma Phi Epsilon National Hazing Policy and the Clemson University Hazing Policy.”

Despite this, SPE sent messages to Clemson authorities seeking permission for the run. When the University did not respond to the request, the fraternity took it as “acquiescence” or approval to do the run and went ahead with the event.

Tucker Hipps’ lawyer filed an amended version of the suit alleging that it had a witness who could corroborate a claim that “defendants King, Carney and Starr forced Tucker to get onto the narrow railing along the bridge and walk some distance on top of the railing. Subsequently, Tucker Hipps went over the railing of the bridge into the shallow waters of Lake Hartwell head first.”

The lawsuit also alleges that “King shined the flashlight on his cell phone into the dark waters below looking for Tucker.”

King, Starr and Carney returned to campus with the other pledges without making any further efforts to discover Tucker’s whereabouts. It was Starr who first notified police in the afternoon that Tucker was missing, more than seven hours after his death, according to records.

“What happens is that fraternities ask people to do small and meaningless things… clean up, or buy beer … things that seem fairly innocuous in nature,” Burnett said. “Then the fraternity asks you to do something that puts somebody at risk, and you can’t say no.”

All parties fully settled the lawsuit with the Hipps family in July 2017. Details of the settlement with the families of King, Starr and Carney were confidential.

The settlement with Clemson stipulated a payment of $250,000 and the endowment of a $50,000 scholarship in Tucker’s name for a Palmetto Boys State attendee to study at Clemson. SPE’s local chapter was removed from campus, but the Virginia-based national organization agreed to educate current and future members about the incident.

“We want nothing more than to help bring closure to the Hipps family, because that is what our values —what virtue, diligence and brotherly love — mean to us,” said Brian Warren, SPE chief executive officer, in a release announcing the recent contribution of $25,000 in reward money.

In response to the Hipps case, the South Carolina Legislature passed the Tucker Hipps Transparency Act in 2016 requiring universities to publicize code of conduct violations by student organizations.

Determined to make something positive come out of a horrible situation, Cindy and Gary Hipps have worked tirelessly to raise awareness about the dangers of hazing. They also established the Tucker Hipps Memorial Foundation to keep their son’s legacy alive.

“I remain hopeful that at some point a witness would be willing to reveal everything that they know,” Burnett said. “Hopefully someone’s conscience would prevent them from going to the grave with information.”

“You can’t force someone to come talk,” said Cindy Hipps, but she remains hopeful. “It’s not just about my healing, it’s [about] their [King, Starr and Carney] healing and the healing of the community. A lot of people want to know the truth.”

“I forgive those boys in my heart,” said Cindy Hipps. “I can’t live [as] an angry person.”

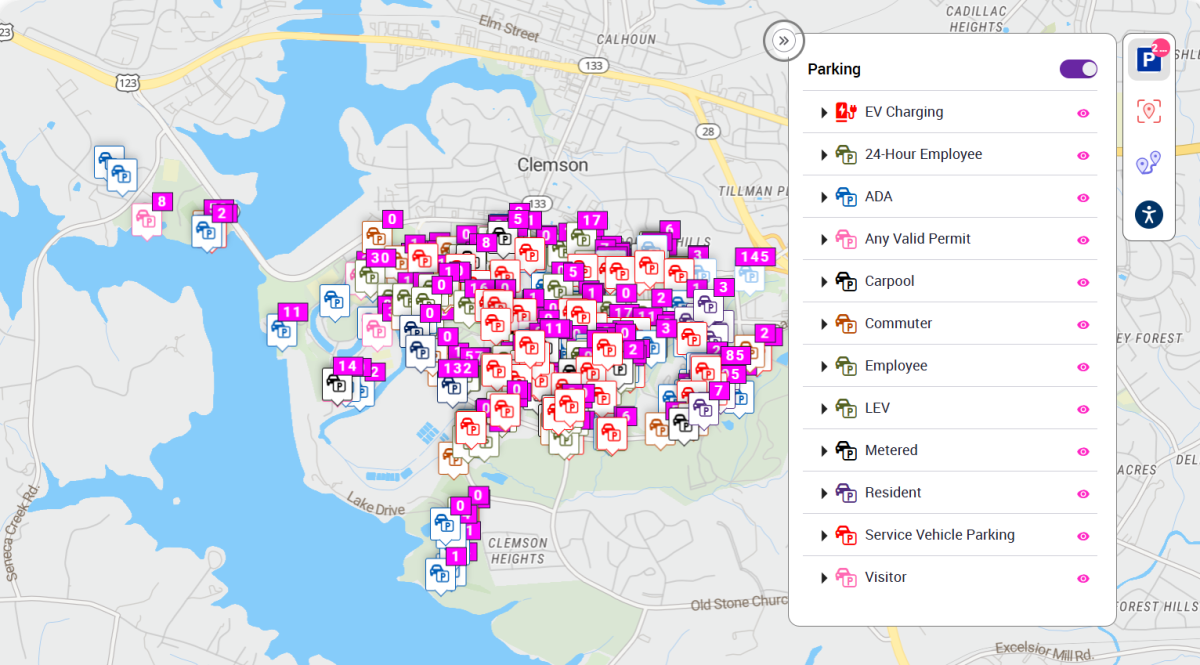

Those who wish to provide anonymous tips can call Oconee County Sheriff’s Office directly at 864-638-4111.

The Hipps family is still waiting for information regarding a case of their deceased son.