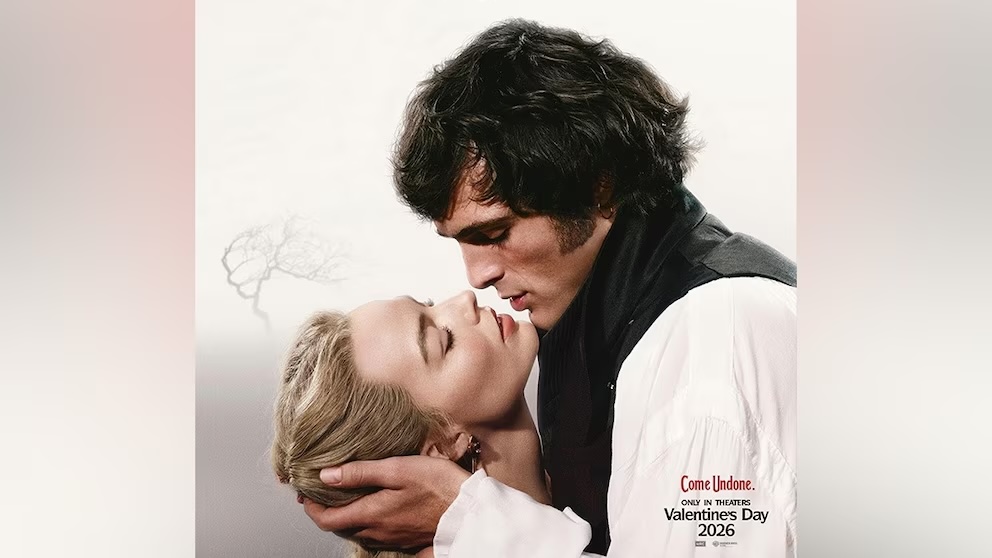

In the second scene of Francis Ford Coppola’s long-gestating magnum opus “Megalopolis,” protagonist Cesar Catalina stumbles onto a scaffold, towers over a model city and manically recites the entire “to be, or not to be” soliloquy from Shakespeare’s “Hamlet.” Adam Driver delivers the legendary monologue with absolute conviction, and Giancarlo Esposito’s Mayor Frank Cicero reacts with rueful derision.

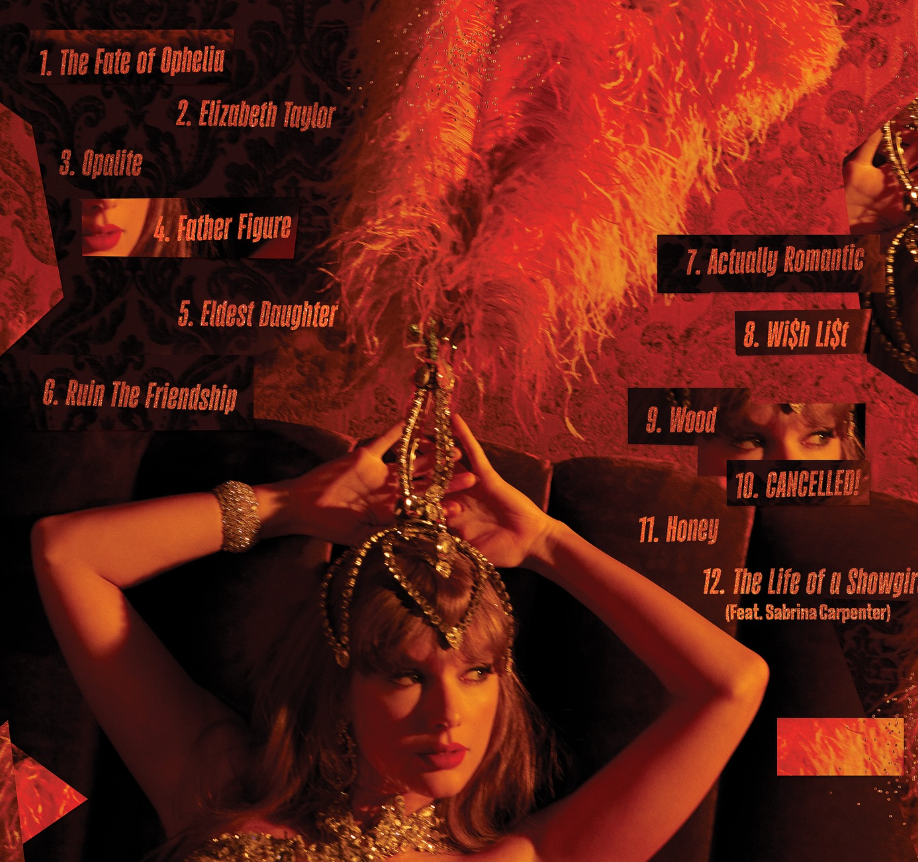

It is a microcosm of the movie: fascinating, beautifully presented and absolutely baffling. The film, which Coppola conceptualized nearly 40 years ago, follows Cesar’s quest to rebuild New Rome — the New York of the future — into the titular Megalopolis, a glowing paradise built from a newly discovered material called “megalon” that has the power to reshape city blocks, clothing and the human body.

Cicero opposes Cesar’s utopian vision, preferring to build casinos and maximize profit and pleasure. Cicero’s daughter, Julia, becomes Cesar’s lover and tries in vain to convince her father that Cesar’s vision is worth fighting for.

Nathalie Emmanuel, who plays Julia, is unfortunately not very good. This isn’t really a judgment of her acting prowess, though — the screenplay is genuinely insane, and the performance style it demands is stilted, strange and demanding.

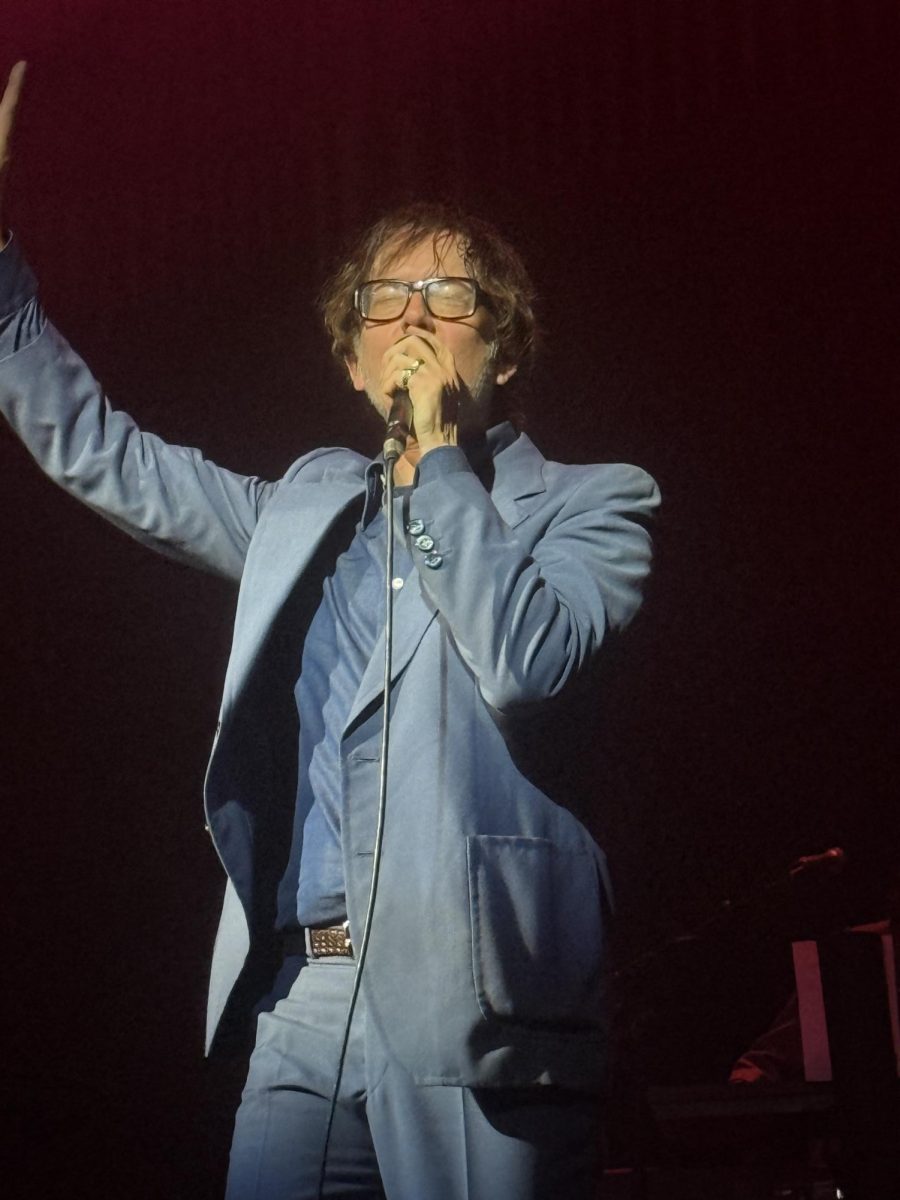

Driver, on the other hand, is fully tapped into Coppola’s weird wavelength, as is Esposito.

Jon Voight, who plays banker Hamilton Crassus, and Shia LeBouf, Crassus’s son Clodio Pulcher, are also kind of incredible. Voight embodies the senile Crassus incredibly well, and LeBouf’s performance matches the script’s bizarre, maximalist energy.

Aubrey Plaza, who plays a character called Wow Platinum, feels like she’s performing the character of an actor giving a performance, which somehow works.

It’s hard to review “Megalopolis” without giving into the temptation of just listing things that happen or appear in the movie.

Jon Voight disguises a bow and arrow by pretending it’s his penis. The end title card is a rewritten pledge of allegiance. There’s a chariot race in Madison Square Garden. Cesar’s plan to revolutionize city-building seems to revolve around replacing all sidewalks with those horizontal escalator things from the airport.

Coppola throws everything he’s got at the audience. It’s a total sensory overload, the kind of maximalism you usually only see in French extremity films but with a distinctly American aesthetic and form.

The most intriguing formal element of the movie is Coppola’s use of split-screen. He frequently divides the screen into three vertical frames, taking montage to its ultimate extent by juxtaposing images directly beside each other as well as in sequence. It’s an incredibly bold choice, and it’s one of the best parts of the film.

Other aspects of “Megalopolis,” though, are not as successful. Despite the two-hour, 18-minute runtime and Laurence Fishburne’s solemn narration, it feels like the movie can’t satisfactorily deliver its entire narrative.

“Megalopolis” keeps dropping plot threads that are never picked back up. Other subplots are mentioned in the beginning and then vanish until the end, while a particularly odd bit about Catalina being able to stop time recurs three times and is never explained or connected to any other part of the movie. It looks really cool, though, and maybe that’s what ultimately matters most.

According to an early title card resembling a slide on a PowerPoint about ancient Rome, “Megalopolis” is a fable. Despite this classification, I have no idea what the moral of the story is, and neither do the two other people I saw it with. Coppola’s narrative is so sprawling and complex that it’s hard to pick out a single unifying idea.

I won’t make the argument that “Megalopolis” is a masterpiece — though some have — but it’s definitely a singular work by a fascinating auteur. If it was a novel, it would be hailed as the greatest since “2666.” See it if you want to view images heretofore undreamt of by man or if you really like the moving walkways at the airport.