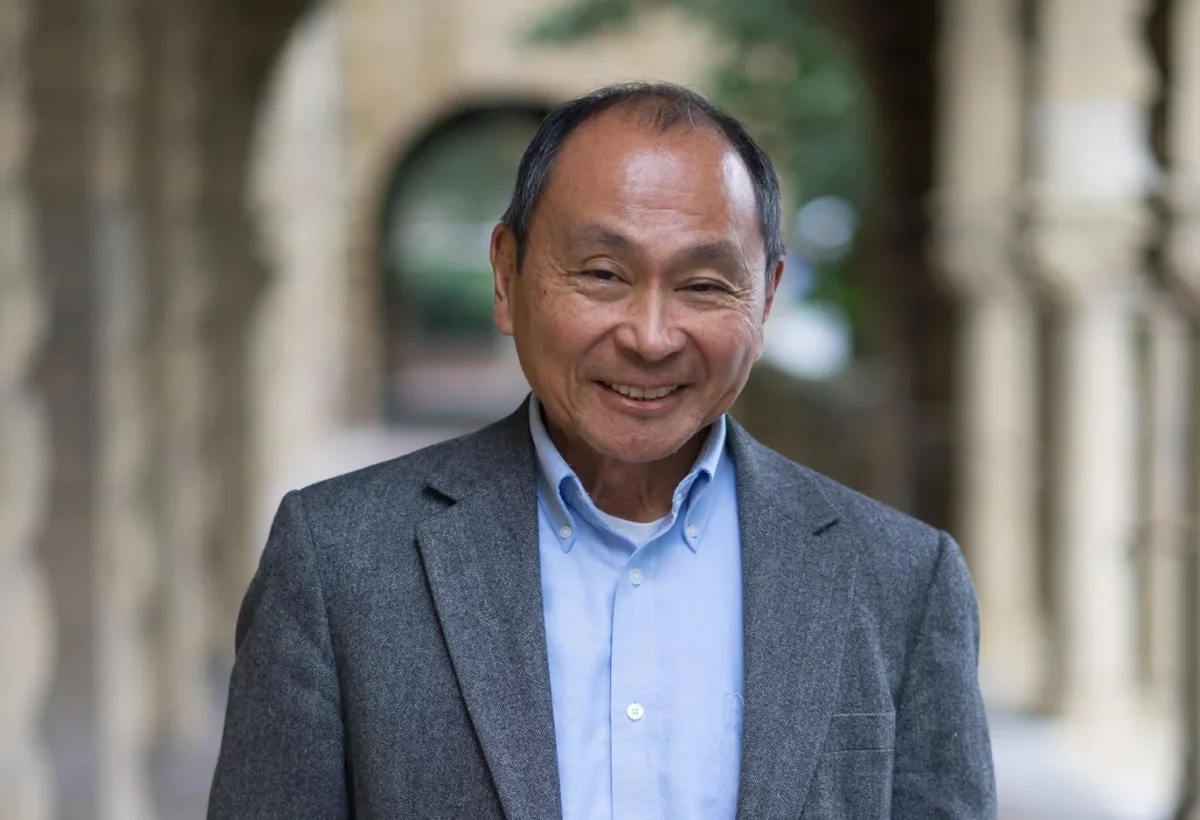

Stanford University’s Francis Fukuyama delivered a lecture regarding the state of global democracy at the Brooks Center for the Performing Arts on Oct. 4.

Fukuyama, the Olivier Nomellini Senior Fellow at Stanford University’s Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, focused his lecture on the “global crisis of democracy” and the “global crisis of trust.”

The lecture event was cohosted by several Clemson organizations, including The Aurantiaco, Clemson’s undergraduate journal for social sciences and humanities, Clemson Libraries, Phi Beta Kappa Society and the College of Arts and Humanities.

Fukuyama emphasized several general facts regarding trends in government. He highlighted the rise of authoritarianism around the world, specifically in Russia and China, as well as an increase in populist nationalism, both leading to a democratic recession.

Fukuyama related his point of populist nationalism to the current election season in the United States. He argued that Donald Trump was not, in fact, the first populist United States president. Fukuyama claimed that Andrew Jackson, president of the U.S. from 1829 to 1837, was actually the first populist leader of America.

Fukuyama stated that the 2024 election “is leading to erosion of the rule of law,” reiterating that populist nationalists use “democratic legitimacy” to enact said erosion.

“There are a lot of things going on that have undermined people’s trust in empirical information and facts,” Fukuyama said.

Fukuyama initially thought that the rise of the internet would be a great thing for democracy, but he eventually concluded that it led to the destruction of trusted intermediaries because “anyone can say anything.” Fukuyama argued that there should be a system of certified information set in place so certain questions are no longer up for debate and cannot have open-ended answers.

Fukuyama also explained the weaponization of social media, detailing how the use of artificial intelligence and surveillance technology can lead to the downfall of “social processes.” With AI, fraudulent images of people and circumstances, called “deep fakes,” can be conjured to make it seem like a certain event occurred when it never truly did. Fukuyama used the example of fake crime footage potentially being presented to authorities to disguise the identities of true criminals.

Fukuyama spoke on the impact of surveillance on society. Nightmare-like surveillance “already exists in China,” he said, where “everybody’s trustworthiness is rated by the government.”

Fukuyama continued describing China’s surveillance climate.

“This became much deeper during COVID because they wanted to keep track of people that had COVID, and they created a much more intrusive surveillance system,” he said.

Fukuyama recounted that surveillance does exist in the United States but at a much more discrete level, namely through Google servers. He explained how Google is able to track where people go, what phone calls they make, what emails they send and so forth.

Fukuyama connected the weaponization of social media to societal awareness. He reinforced the idea that people only get their news from influencers with thousands of followers on social media platforms rather than from concrete sources that provide factual information.

“Liberalism can’t sustain itself unless you have active citizenship,” Fukuyama said. Active citizenship, he said, is when “you pay attention, follow public affairs and are willing to get involved, even in the simple matter of going to the polling place on election day.”

Fukuyama ended his lecture by thanking the organizations in charge of the event before taking questions from students and staff.