Chances are you’ve already heard about “Sinners,” the latest film by “Black Panther” director Ryan Coogler. It has been receiving a level of unanimous and passionate praise from both critics and audiences that I don’t think I’ve seen since “Oppenheimer,” and I was pleasantly surprised to find that it lived up to the hype.

“Sinners” is an easy pitch: twin brothers, played by Michael B. Jordan, attempt to start a juke joint after returning to their hometown in the Depression-era South, but run into supernatural trouble.

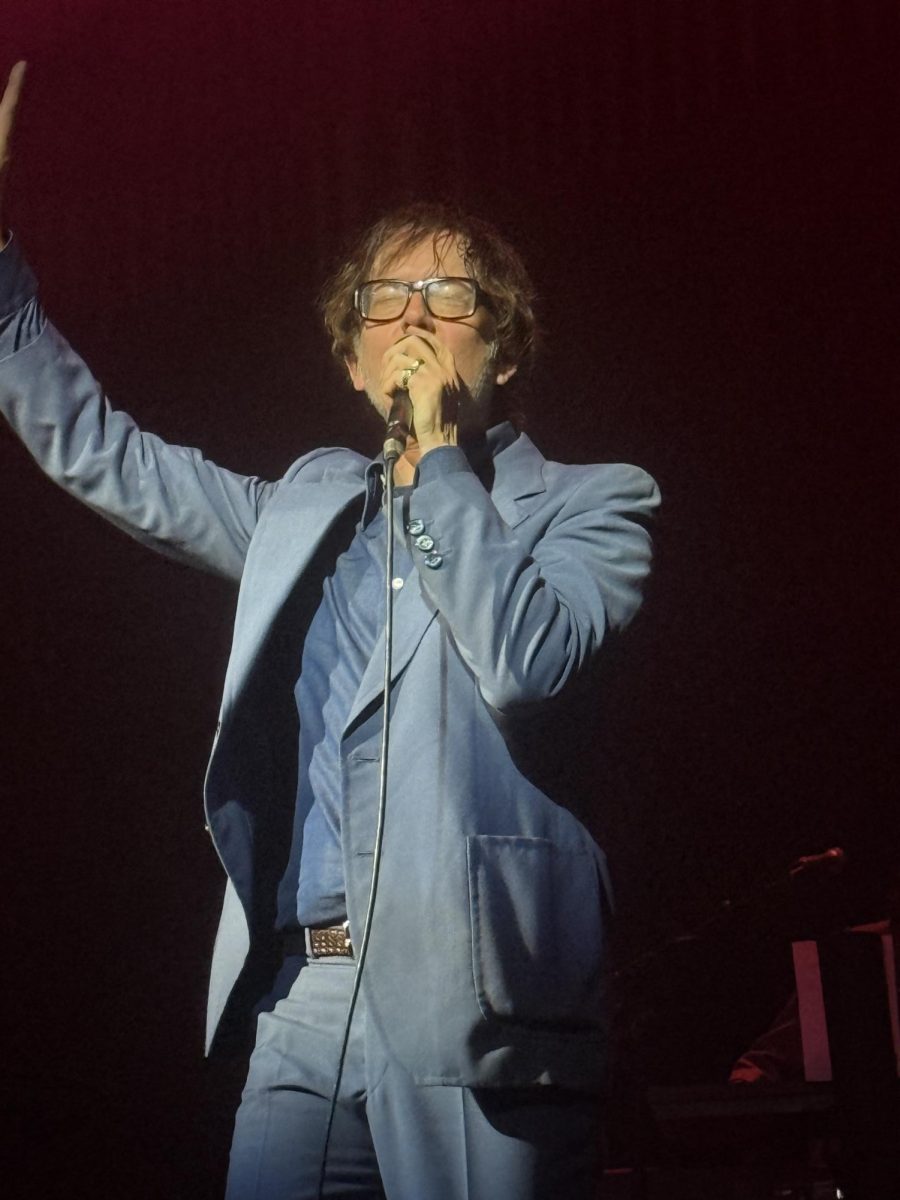

Jordan is reliably excellent in his dual role as the “Smokestack Twins,” but 20-year-old newcomer Miles Caton runs away with the movie. Caton, who plays Sammie, the twins’ cousin, has a quiet baritone voice that he puts to great use in the film’s many musical sequences, singing the blues like a man with decades more life experience.

Music is one of the most essential parts of “Sinners,” which may be surprising to viewers expecting a gory vampire action movie. There’s plenty of gore and action, of course, but it’s deftly interwoven with transcendent musical sequences. The film’s most memorable setpiece isn’t a shootout or explosion, it’s a sweeping long take that surveys the juke joint’s reaction to Sammie’s incredible musicianship.

His playing and singing are so powerful that they bend the fabric of time, bringing together Sammie’s musical ancestors and descendants. The sound mixing, cinematography and ensemble performance combine to elevate the scene to greatness.

Sammie’s musical talent is dangerous, though. His playing attracts a folksinging Irish-American vampire, Remmick, who wants to convert the whole town to vampirism so that they may revel eternally.

“Sinners” strikes a rare balance between populist spectacle and thematic complexity, and much of that success is dependent on the music. The blues music and Irish folk that soundtrack the film both represent different kinds of cultural assimilation.

The blues originated in African-American communities in the early 20th century, drawing on Africa’s rich and diverse musical traditions. It’s a uniquely Black genre of music, but one that subsumed into the broader, white American cultural milieu. The tradition of juke joints that the twins participate in, for example, was gentrified and became the honky-tonk bar.

Sammie is a compelling character because he is torn between expressing his exceptional talent and love for his music and risking the loss of his cultural identity.

The most obvious path for Coogler would have been to make Remmick an avatar of whiteness, but he complicates the traditional racial paradigm by writing an Irish character. The Irish were stripped of their culture and religion in a similar fashion to African-Americans, a fact that Remmick brings up repeatedly.

He insists that if the Black characters were to simply join in and assimilate, becoming part of this homogenized, depersonalized supernatural culture, they will be happy forever, at the cost of their souls.

The difference between Remmick and the film’s protagonists, of course, is that the Irish were able to assimilate and eventually become regarded as white, which was impossible for African-Americans.

His promise is seductive but illusory, and the film’s protagonists grapple with it in a thematically and dramatically compelling fashion. “Sinners” enthusiastically participates in the genres of action and horror throughout its last hour, finally fulfilling its promise of considerable blood and guts. The comparative slowness and relative mundanity of the preceding hour and a half make the eventual turn to violence hit even harder.

I don’t think “Sinners” is a masterpiece, as many seem to, but it’s very, very good. It’s certainly greater than the sum of its parts, overcoming whatever minor issues I may have with the film through its combination of stellar acting, strong writing and impressive cinematic craftsmanship.