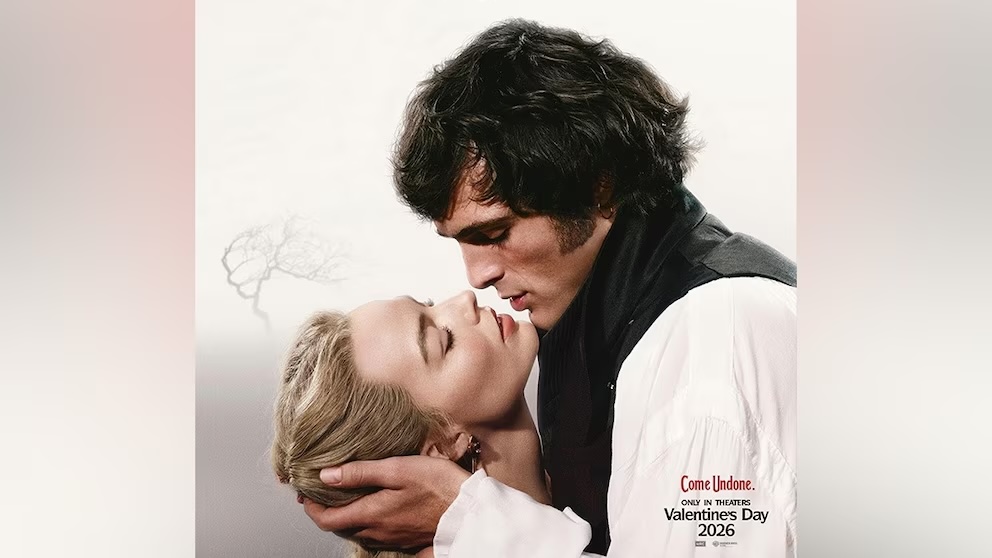

There are few accolades as tired and hackneyed as calling a film “the movie we need right now.” Aside from the fact that timely themes don’t inherently constitute a good movie, the films burdened with the label often fail to meet the current moment head on, or in some cases have no actual interest in doing so. Paul Thomas Anderson’s new film, “One Battle After Another,” is the exception.

Anderson understands that the best way to reflect the present is to visualize the future — about 20 minutes into the film, voiceover tells us that 16 years have passed, but “not much has changed.” Anderson shrewdly recognizes that the scariest kind of dystopian future is one that looks eerily similar to our present.

This idea is, to some extent, carried over from Thomas Pynchon’s 1990 novel “Vineland,” which “One Battle After Another” is loosely adapted from. While Anderson’s film is less sprawling than Pynchon’s novel, it borrows the overarching story of a former revolutionary attempting to rescue his daughter from a repulsive, sadistic military man.

It also adopts Pynchon’s absurd sense of humor — the military man in question is a member of a top-secret society of white supremacists dedicated to the worship of Santa Claus, a concept that’s so Pynchonesque that I almost can’t believe it’s an Anderson invention.

The absurdity of “One Battle After Another” does not, however, blunt its cutting edges. Pynchon’s book is very much a product of its time, an early ’90s reflection on the ravages of the Reagan era and the failures of ‘60s new left radicals. Anderson’s film recontextualizes the narrative to focus on a family facing down the force of a violent, militaristic United States enabled by the failures of the revolutionaries of today.

The film centers on Leonardo DiCaprio’s Bob Ferguson, a onetime munitions expert who has become a bumbling stoner, and his daughter Willa. Bob has raised Willa alone after her mother, the hilariously named Perfidia Beverly Hills, sold out her revolutionary cell in a bid for government-afforded freedom. Bob is forced to reckon with the aftermath of the failed revolution after Lt. Col. Steven J. Lockjaw, an insane military careerist who raped Perfidia just before Willa was born, kidnaps Willa to try and erase any evidence of his potential racial impurity.

Despite the film’s absurd tone, the anxieties and disturbing trends that it reflects feel very immediate and unsettlingly real. Anderson opens the film with a revolutionary raid on an immigration detention facility that’s rendered in impressive detail, disturbingly analogous to both the current administration’s newly constructed “Alligator Alcatraz” and the preexisting facilities built during previous presidents’ tenures. This integration of recognizably contemporary but still unquestionably evil locations and symbols is key to the film’s success.

Anderson has said that “One Battle After Another” has been a long-gestating project — he’d been taken with “Vineland” when he first read it, and became obsessed with the idea of making a film based on Pynchon’s novel, but couldn’t quite figure out how to make it work. He credits becoming a father with helping him understand the book’s emotional core.

Anderson and comedian Maya Rudolph are parents to four children, which implies a personal component to some of the changes that he makes in translating his source material. In “Vineland,” the central characters are all white, and there’s very little acknowledgement of the role that race plays in America’s radical politics. “One Battle After Another,” on the other hand, is about the relationship between a white father and his mixed-race daughter. It’s hard not to read this change as an act of personalization — Anderson himself is the father of a mixed-race daughter, and if “One Battle After Another” is anything to go by, he’s not thrilled by the state of the world that she’s growing up in.

It’s easy to read “One Battle After Another” as cynical. The revolutionary vanguard is ineffectual, the tyrannical government triumphs despite their moronic incapacity and nothing substantial has really changed by the end of the movie. Despite all this, though, I think it’s a fundamentally hopeful movie. The revolution may fail, but its failures will form a bedrock on which the next generation can take back the world from the tyrants holding it hostage.